17/10/2021

17/10/2021

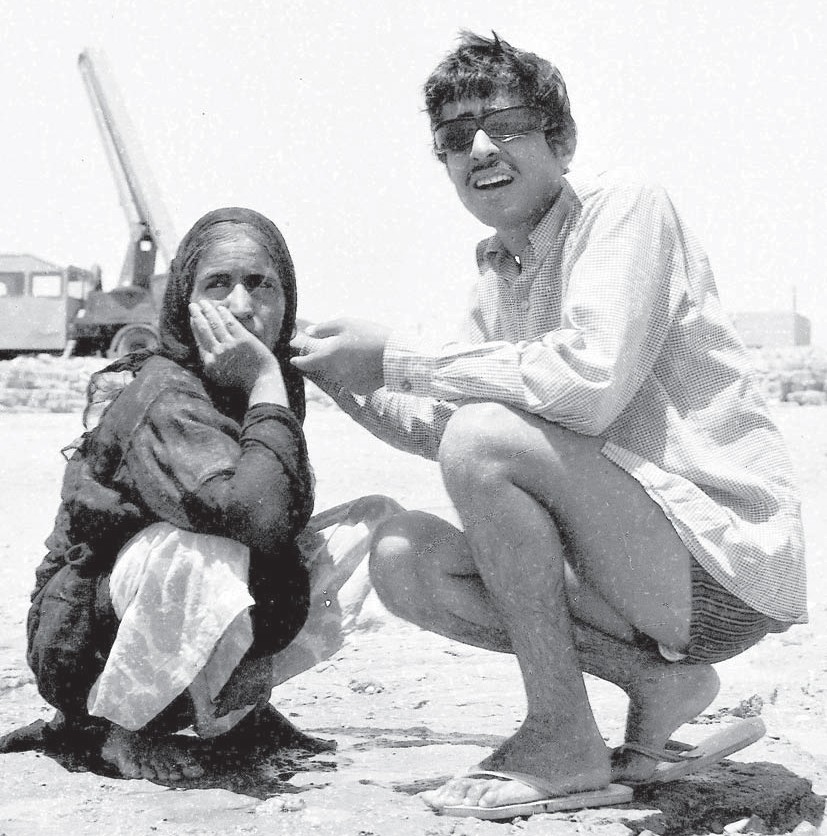

A rebel called to fame

I met Khaled Siddik some years back for an exclusive interview with Arab Times. We spent many hours discussing his life, his work, the many challenges he faced, his disillusionment with the system, which he felt was not as supportive of creativity as it should be, and his support of young Kuwaiti talent. We formed an instant connection, more so because of my nationality. Khaled Siddik spent his growing up years in India. It is there he received the foundations of his education. The Indian connection continued when he worked with Indian film greats like Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen, Adoor Gopalakrishnan as jury members at various international film festivals in his later years. A few years back, he was honoured with a Lifetime Achievement Award by the Indian Business & Professional Council in Kuwait. A pioneer in filmmaking, Khaled Siddik’s 1972 Oscar-nominated movie ‘Bas Ya Bahr’, the first film to be directed and produced by a GCC citizen, won the prestigious FIPRESCI award at the 1972 Venice Film Festival. Later, he made several notable films such as the ‘Wedding of Zain’, ‘The Last Journey’ and ‘Faces of the Night’. Disheartened by a lack of support and patronage, Khaled Siddik began spending more time in Europe making documentaries. With his death on Thursday, Kuwait lost one of her greatest sons. Not only was he a pioneer of regional cinema, he was also a mentor to many upcoming filmmakers who flocked to his home in pre-Corona days for discussions and mentoring. Arab Times pays tribute to the iconic filmmaker with an in-depth interview we did a few years back.

Khaled Siddik was a pioneer in the field of fine arts and motion pictures in Kuwait and the Arabian Gulf. An internationally acclaimed filmmaker, he was a writer, producer and director. Siddik had a Master of Arts degree in Radio/Television Administration and Production from Chelsea University. Later, he went on to do his PhD in Motion Pictures. As a filmmaker, he trained in Italy, U.K. and the U.S.A. Over the years, Khaled Siddik received several awards and recognitions. In 2000, he was unanimously elected Chairman of the first Association of Gulf Film Makers. In 2009, he received the Lifetime Achievement Award at the Dubai Gulf Film Festival. In 2012 he was honoured at the First GCC Film Festival in Doha, Qatar. Throughout his career, he authored several books, newspaper articles, articles and discourses on movie making. He participated in several International Film Festivals in New York, Chicago, Golden Globe — CA, Montreal, Venice-Italy, London, Spain, Paris Cannes, Moscow, Tashkent, Karlovy Vary, Prague, Hong Kong and Fribourg — Switzerland. He was a member of the Jury at the Soussa Festival Tunis (1999), President of the Jury at the Paris Fest (2000) and Member of the Jury (Tehran Intl Festival (2003). Throughout his life, Siddik was a rebel and refused to conform. He flouted conventions and pursued his creative dreams and, while doing so, surmounted several challenges, both personal and professional.

In 1971, Siddik co-wrote, produced and directed ‘Bas Ya Bahar’ or ‘The Cruel Sea’, the first full-length award-winning feature film in the Gulf. The film won 9 international awards, including Silver Lion Award — Venice Film Festival (Italy). He followed it up with ‘The Wedding of Zein’ in 1976, which won an award at the Cannes. Over the years, Siddik became a force to reckon with in the field of motion pictures. Despite many award-winning films to his credit, ‘Bas Ya Bahar’ Siddik’s first feature film was special. This film made history. It made history as the first film to be produced in Kuwait, it made history as the only film to date to depict the life of pearl divers, it made history by winning nine major international awards, and it made history because it was made at a time when there was no culture of filmmaking in the Arabian Gulf. What is interesting is that this illustrious Kuwaiti filmmaker had a close connection with India. He spent his formative years in Bombay, where he picked up the rudiments of the craft and later continued to be inspired by Indian filmmakers. In his interview with Arab Times, Khaled Siddik shared the story of Kuwait’s first film, his journey as a filmmaker and the predicament of the present generation of Kuwaiti filmmakers.

Arab Times: What brought you to filmmaking? There was no precedence of filmmaking before you in Kuwait.

Siddik: In fact, at that time, there was nothing here in Kuwait. I learned filmmaking in India. As a six-year old, I studied at the Sharqiya School, where we had a very tough headmaster named Ahmed Saqqaf. He knew nothing apart from caning (laughed). Gradually, I and few others decided to skip school. During school time, we would hide in the cemetery next to the school and trap birds. It went on fine for some time, but then my father caught me twice coming out of the cemetery. The third time it happened, he put me on a steamer to Bombay. He had offices in Bombay, and he told them to get me the best education. I studied at St Peters High School in Bombay.

AT: Did you have problems adjusting to life in India?

Siddik: In the beginning, it was tough. I knew no language apart from Arabic. I knew neither English nor Hindi nor Marathi, which I had to learn later.

AT: So what brought you to filmmaking?

Siddik: As I said, it was tough at the beginning to be cut off from my world. My analysis of the situation is that movies were probably a sort of escapism for me. Movies probably disconnected me from my miserable life. I was crazy about movies. On weekends, I watched American movies, Hindi movies and British movies. Later at the age of 12, I started visiting the Central Studios, which belonged to Guru Dutt. Gradually I was allowed to join as an intern.

AT: What kind of work did you do?

Siddik: I did everything. I did the work of a carpenter. I worked in the laboratory. Basically, I did the job of an office boy. Later, I also attended a movie-making class at the ‘Photo Kala Mandir’, where I learned a lot.

AT: Were there other filmmakers in Kuwait when you started making films?

Siddik: No, I was the first one. In fact, we didn’t even have the equipment when I came back to Kuwait in 1961. I had a big row with my father, who wanted me to join his business. I left him and joined Kuwait Television, which had just started.

AT: What was your experience with KTV?

Siddik: There was nothing in Kuwait TV then, no equipment, no knowhow. I taught myself TV production, and gradually after a year I started persuading the supervisors and the undersecretary to buy movie equipment. I did some short films for Kuwait Television. In 1964, I directed Aliawassam, the first-ever Gulf production. It was about 20 minutes in length. In 1965, I made a documentary on falconry. I made other short movies until 1971 when I directed ‘Bas Ya Bahar.’ I produced the film as the government was not ready to finance feature films.

AT: Why?

Siddik: Because we had no experience. Because they thought it was not that important. There were many excuses, and I could not wait. I had to do it. AT: Where did you show your short films?

Siddik: The short ones were shown in theatres as a sideshow.

AT: What challenges did you face in your initial years?

Siddik: The main challenge was with mentalities. I had a tough time with the Parliament after the release of ‘Bas ya Bahar’. The Parliament wanted to ban it. They tried to ban and burn the negative. They thought it was a disgrace to show how poor Kuwaitis were. But that was the reality. And they should have been proud that Kuwait went on to be so wealthy. Many people don’t understand that. But, unfortunately, in those days, some of the very wealthy MPs didn’t want to remember their old ‘poverty’ days.

AT: How did you manage to release the film?

Siddik: In those days, HH Sheikh Sabah, our present Amir, was the Minister of Information. He was an open-minded person, and he supported me.

AT: Apart from the mentality, what other challenges did you face?

Siddik: We did not have enough technicians. Funnily enough, I did not have assistant directors. I had only one cameraman, and we helped each other. Later, I appointed one assistant director to share the load. Usually, directors have three or four assistants, but I thought I could make do with at least one. But after twenty days, he disappeared. He couldn’t take the load. After a time, I got another one, and this guy disappeared as well. So I had to finish the film without an assistant director. After all, I was taking the entire risk. It was my money, my reputation, and my dream on the line.

AT: What was the local response to the film?

Siddik: It was unheard of. We had an unbelievable response. HH the Amir, God bless his soul, Sheikh Jaber al Ahmad called me to his office and said, “I heard people are being taken to the movie on ambulances from the hospital.” I told him I was not sure, so he asked me to find out and let him know. I started watching people come into the theatre, and I found that it was true. They used to bring people on wheelchairs and ambulances for the movie. In fact, it was the first time in the history of Kuwait that a film ran for about six weeks.

AT: Why do you think people reacted the way they did? Is it because it was the first Kuwaiti film?

Siddik: Because I think it was very authentic not just from the point of view of the storyline or the dramatic content, but I was also conscious of other things. I included the social lives and economic lives of people. The film had real, anthropological songs of marriage. Nothing was superficial. In that sense, the film was rich. The other aspect was that this was the first movie to be shot underwater ever in Asia. That was the greatest risk I took. In fact, I didn’t know how to do it till the last minute. I made the film in black and white. Commercially speaking, the film should have been in colour, but I felt colour did not exist before oil. Kuwait and the Gulf was a dull, poor community and the best way to express this would have been in black and white.

AT: How special is ‘Bas Ya Bahar’ to you as a filmmaker and Kuwaiti?

Siddik: There was no experience in filmmaking in Kuwait, and so I had to finance, produce, direct, write and distribute the film. When the movie was ready, I met several distributors around the Arab world, but they wanted stars in the movie. I could have had stars, but I knew that the Kuwaitis would not accept an Egyptian star as a pearl diver. I needed to have real Kuwaitis. When all of them turned down my movie, I played the trick through festivals. I started participating in festivals around the world, and it clicked. Continuously, the film picked up award after award. Two years later, the Arab distributors contacted me, but I told them it was too late. I also introduced the concept of a director’s movie and not a star’s movie, because in the Arab world even today, movies are star-driven.

AT: Are you in touch with young filmmakers of Kuwait?

Siddik: Once a year, I invite young filmmakers over. There are about 25-30 of them. They make short movies and I have a screening room upstairs in my home. Some of them tell me that their father helped them make their film sets. I tell them I would like to meet their fathers and tell them what my father was like. (laughed)

AT: Maybe things have changed. Your father belonged to a different generation.

Siddik: But he was a traveller compared to other Kuwaitis. All his life, he travelled for his business. You don’t expect this kind of mentality from someone like him. I thought he would support me.

AT: Did you leave Kuwait television after ‘Bas Ya Bahar’?

Siddik: I wanted to resign, but they did not allow me because I represented Kuwait in conferences and festivals worldwide. They asked me to go ahead and make movies. I said I would if they financed my films, and I would quit without any real support.

AT: Did they support you?

Siddik: No.

AT: Why?

Siddik: I don’t know. It is hard to say. Were they not civilized people? After all, it was good propaganda for the country.

AT: So you financed your films?

Siddik: All of them.

AT: How did you do it?

Siddik: I had my resources, and when the movies were sold, I made others. My concept of movie-making was for the international market, and it clicked. My friends who are into filmmaking abroad think there is a lot of money in Kuwait. I tell them, yes, there is money, but not for movies.

AT: So you made films for the international market?

Siddik: Yes. That is how it sold. And that is how I could survive and make more movies.

AT: What were the other problems you faced as a filmmaker?

Siddik: Earlier, the filmmakers faced the problem of monopolies of screening in Kuwait. It was all run by one company, take it or leave it. But that monopoly ended a few years back.

AT: Did you work on any collaboration?

Siddik: I did once. But while collaborating, they expected me to pay 80% because I was from Kuwait. I tell you, it is a real problem being a Kuwaiti.

AT: What was your experience like at international film festivals? Did you face any discrimination when you attended these festivals?

Siddik: Yes. I was discriminated against at some festivals.

AT: Why?

Siddik: The main problem is that I am from a rich country. They think I have oil wells. Whenever I go to shoot a movie, the price goes up because I am Kuwaiti. Only educated intellectuals like Satyajit Ray understood the situation. For instance, in 1972, ‘Bas Ya Bahar’ was nominated at the first International Festival in Tehran. Ray was a jury member. Later, I heard that Mr Ray was the only person who fought for my movie.

AT: I think you once shared an award with Ray?

Siddik: Yes, ‘Bas Ya Bahar’ shared an award with Mr Ray’s ‘Seemabadha’ in 1972 at the Venice International Film Festival.

AT: Do you still direct and produce?

Siddik: I do produce in Europe, but I do so under a pseudo name.

AT: Why do you use a pseudo name?

Siddik: Many reasons. After the invasion of Kuwait, my studios were looted and destroyed, and I had issues with compensation. But I do work now to kill time, and these are not the kind of movies I would like to have my real name on them. Sometimes I write movies that I sell.

AT: You started making movies in the sixties. Do you see any difference between then and now?

Siddik: Censorship has become a significant problem. Earlier, censorship was government-driven. It was much more flexible and lenient. But now, unfortunately, censorship is bad because of interference from the Parliament. It is a very sad issue. At times, I show the young filmmakers my earlier movies, and they get really surprised. For example, in 1968, I made a short movie called ‘Faces of the Night’ where I showed a woman in a nightgown just above the knee. There is another scene where I showed a table with playing cards, different kinds of scotch whiskey with a gun, and a drunken guy. When they see these scenes, the young filmmakers marvel, they say, “Oh! Were you allowed to do this?” I tell them that these films were all produced by Kuwait Television. Today these things are not allowed. That is one reason I don’t want to make any more movies here because I feel handcuffed. I believe in self-censorship. I know where I stand and what the red lines are. These people we have elected democratically are forcing censorship on us. Censorship is a form of dictatorship, and Kuwait is a democratic country. It is unfortunate.

AT: Is that a reason Kuwait has not developed a film industry of its own?

Siddik: The biggest problem is getting finance. I feel sorry for these young filmmakers, and I do not know how to help them. They make commercials, and they make movies with whatever they make out of those commercials. Some of their films are beautiful, but they still go around begging for money. And these short movies do not make money. Despite the technological advancements, the young filmmakers are in bad shape.

AT: How do you see the future of filmmaking in Kuwait?

Siddik: Well, it will go on like today, unless the government decides to develop this. The situation is unfortunate in the Gulf. I hope the situation in Kuwait changes and more finance is made available to filmmakers. However, we must also remember that there are strings attached when it is the government’s money.

AT: How do you look back at your journey?

Siddik: I had dreamt of paving the way for a full-fl edged movie industry, but everything is going the wrong way. However, I have enjoyed every moment of my journey. At times, I feel I could have done more, but then I would have had to sacrifice quality, which I was not ready to do.

By Chaitali B. Roy

Special to the Arab Times