18/08/2022

18/08/2022

A huge, old wooden chair held together with pieces of chord, balances on just two legs on top of a red carpet in the middle of the room. Draped across the back of the chair is a black bisht, the traditional cloak with gold embroidery that’s worn for formal occasions by men throughout the Arabian Gulf.

The broken chair with the bisht is an exhibit in Kuwait’s Museum of Modern Art by Kuwaiti artist Ambar Waleed. It’s thought-provoking in its simplicity and it’s obviously designed to make a strong statement, but about what? The powerful message becomes clear when explained by Museum Manager, Ahmed Al Babtain.

In Arabic, a chair conveys the meaning of an official position while a bisht is a symbol of authority. “You know how it is when someone stays in their position for too long? They don’t want to give it up and give someone else a chance, even though they’re no longer doing a good job. That’s the theme of this exhibit.” Kuwait’s Museum of Modern Art, with its wide-ranging collection of paintings and sculptures, is an ideal place to contemplate hidden meanings.

It’s housed in the old Sharqeya School at the back of a vacant lot opposite Souk Sharq. With its spacious sun-splashed courtyards, pleasant shaded arcades, and cozy surrounding rooms, it’s an inviting setting. Strategicallyplaced wooden benches beckon to the visitor to pause and enjoy the visual feast. The museum opened in 2003 under the jurisdiction of the National Council for Culture, Arts and Letters (NCCAL). Promoting the arts in Kuwait, stimulating interest in Kuwait’s cultural heritage, and restoring and maintaining local historical buildings are among the activities of this organisation.

The establishment of the Museum of Modern Art in the old Sharqeya School fulfilled all these goals. Sharqeya School was built in 1939 and served first as a primary school for boys and later as a girls’ primary school. Several of Kuwait’s former Amirs were among its notable students. Plans to convert the building into a museum were already in place when Iraqi forces invaded Kuwait in 1990. During the occupation, Iraqi troops vandalized the building, leaving it a shambles. The NCCAL carried out a careful restoration aimed at retaining the building’s original features and character.

The traditional ceilings of mangrove poles and palm frond matting were replaced. All the woodwork, including the window frames and doors, was redone in the original style. Even the typical old-fashioned, opaque patterned glass characteristic of old Kuwaiti houses was used for the window panes.

The few concessions to modernity include a glass elevator, free-standing exhibition panels and a glass-roof over the main courtyard allowing guests to linger in air-conditioned comfort. Upon entering the main courtyard, visitors will see four large paintings depicting some of the pioneers of the formative arts movement that thrived during Kuwait’s golden years from the 1950s through the 1980s. Many of these artists received professional arts training abroad under the sponsorship of the Kuwait government. Their work is featured in the museum.

Sculptures

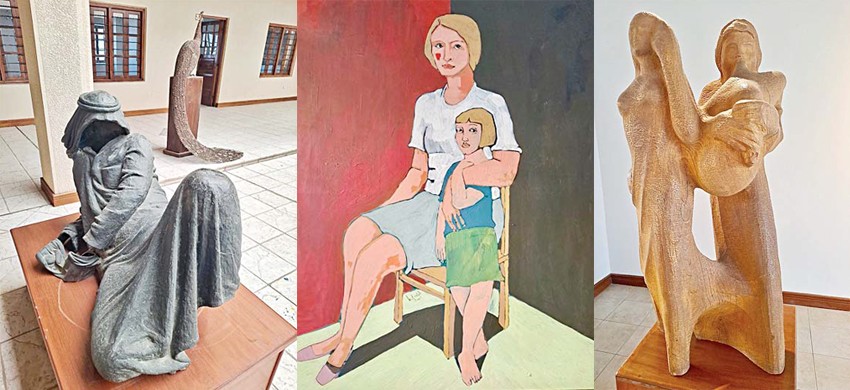

Among them is Sami Mohammad, whose sculptures are on display in the courtyard. In the early 1970s he worked primarily in wood. Stemming from this time is a series on human procreation that includes four sculptures: Before the Delivery, The Delivery, After Delivery, and Mother with her Child. These rounded, gentle shapes are in stark contrast to another series of his sculptures on the other side of the courtyard titled An Attempt to Get Out.

Created in 1978, these sculptures are extremely disturbing. They deal with the concept of a man entombed within a solid block of bronze. The hands appear to have punched their way out of the massive block and are reaching out in a pitiful plea for help, while bulges just under the surface suggest the rest of the struggling body that’s trapped inside. Writing in Kuwait: Arts and Architecture, Arlene Fullerton sheds some light on the message these sculptures are meant to convey. “Sami Mohammad uses his art to speak about humanity. His figures are all victims. They are bound, crushed, tortured and entombed and yet while there is the merest thread of life, they do not give up hope. He glorifies man’s strength, persistence and will to free himself from his struggles.” Ahmed Al Babtain admits that storyboards and extended captions explaining the exhibits could do much to help visitors gain a better appreciation of the museum’s art. “We’re planning to add descriptions,” he says. “And every six months we change some of the exhibits and bring in new art, in order to make things more interesting.” Another notable Kuwaiti sculptor whose works are on display is Khaza’al Al Qafas. His life-sized bronze sculpture, The Relaxation, was created in 1979.

It depicts a faceless man wearing a dishdasha reclining in a casual posture. A young Kuwaiti man examining the sculpture marvels at how realistically the folds of the man’s robe are draped, although they’re made of bronze, and at how the figure exudes an air of peaceful repose. “It’s such a typical pose, there’s always some guy in the diwannia who’s relaxing like this,” he laughs. Other sculptures by Al Qafas provide vignettes of life in days gone by. The Afternoons (bronze, 1983) also depicts men in dishdashas in typically relaxed positions. This time they’re sitting on a bench in a scene of easy camaraderie, the way old men used to spend their afternoons in the old days, sitting facing the sea and watching the world go by. Al Jerbah (bronze, 1981) is a sculpture of a type of goatskin bag once used to store and transport fresh water brought by ship from the Shatt Al Arab River in Iraq.

The Habban Dance (wood, 1978] is a sculpture of two graceful elongated figures, a man and a woman. The man is playing the habban, a traditional goatskin bagpipe, his cheeks puffed up with the effort of blowing into the instrument. In bright, spacious rooms surrounding the ground floor courtyard, and on the first floor, paintings and sculptures are displayed in pleasant juxtaposition. Various aspects of Kuwaiti heritage are popular themes. Al Seef Palace at Sunset is a painting by Tareq Sayed Rajab. It shows the old dhow harbor next to the palace filled with wooden ships, their jumble of masts silhouetted against an orange sky and reflected in the water. Look closer and you’ll see the paraphernalia of the shipbuilder’s trade: a capstan, scaffolding, piles of wood, and roller logs used for launching the traditional vessels. In the background is the iconic shape of the Seef Palace clocktower. Tareq Sayed Rajab was a man of many talents who made a profound impact on Kuwait.

Painter, photographer, ceramic artist, archaeologist, scholar, educator, and heritage preservationist; with his wife, Jehan, he founded the Tareq Rajab Museum and the Tareq Rajab Museum of Islamic Calligraphy as well as the New English School. A number of other artists have also depicted scenes from Kuwait’s age of sail. Ahmed Al Babtain recalls that a group of American soldiers visiting the museum wanted to know why there are so many paintings of wooden boats. He explained that in the pre-oil era, shipbuilding, pearl diving, and trading voyages down the Gulf and over to India and East Africa were the mainstay of Kuwait’s economy.

Ayoub Al Ayoub is another one of Kuwait’s distinguished art pioneers whose work highlights Kuwait’s heritage. A prolific artist, he has painted more than 600 works depicting traditional Kuwaiti scenes.

His painting, Elementary School Certificate Test, shows boys in a traditional classroom being supervised by a dishdasha- clad teacher. Like many of his contemporaries, Al Ayoub also served as an art teacher in government schools. The Khalal Seller, by Essa Saqer, illustrates a traditional scene that can also be observed today, especially at this time in the summer season when fresh dates are ripening and are being sold in the market. Khalal is the Kuwaiti name for dates when they are freshly-picked and still hard and crunchy. Another bustling market scene is Souq Wajef by Ibrahim Ismail, an impressive long panel showing the shaded alleyways of Mubarakiya market.

Many talented Kuwaiti women have also made their mark in the art world. Among those represented at the museum are the award-winning painter and writer, Thuraya Al Baqsami. Her abstract painting, The Talisman of Love, can be seen on the second floor. Nearby is the painting Monday Morning (2) by Sabeeha Beshara, in which a woman wearing red-colored traditional dress sits looking calm but expectant in a red-colored room, making one wonder what she’s anticipating. Mother and Daughter was painted in 2001 by the internationally- acclaimed artist Ghada Al Kandari. Powerful women are a common theme in her work, and the mother with her arm wrapped protectively around the shoulder of her daughter exudes quiet strength. You can see more of Ghada’s paintings on her fascinating blog called Pretty Green Bullet, where she shares her work and her thoughts.

Events During the long summer season, things are quiet at the museum and chances are if you visit, you’ll have the whole place to yourself. According to Ahmed Al Babtain, workshops and special events and exhibitions are being planned for the autumn. You’ll be able to get news about them, and all National Council for Culture, Arts and Letters activities, by following their Instagram @ kw_nccal. Kuwait’s Museum of Modern Art, like modern art museums the world over, awakens public interest in art, encourages critical thinking, and provides material evidence of the human condition that’s open to questioning and discussion.

It’s unique in its unpretentious setting. The simple architectural lines of the traditional building enhance the vibrant colors, bold shapes, designs, and textures of the paintings and sculptures. Visit and immerse yourself in the artists’ world of storytelling, where traditional themes and changing cultural ideas and social concepts are open to the viewer’s interpretation. The museum is open weekdays from 9:00 a.m. to 8:30 p.m.

Story & Photos by Claudia Farkas Al Rashoud

Special to the Arab Times